Today’s post is AI-heavy! AI as in OCR (“optical character recognition”). We will OCR (“optical character recognize”) a hex listing for a Prolog interpreter (which used to be thought of as an “AI language”) for the Commodore VIC-20! (As a bonus, some small parts of the tools I made to verify the OCR transcription were written by ChatGPT.)

As you may have heard before, OCRing stuff is error-prone. Ls and Is and 1s being mixed up makes natural language texts annoying to read, and program listings almost useless, because you’ll spend a long time trying to find the error. Why does this take a long time? Because our eyes (and attached circuitry) don’t notice tiny imperfections in a sea of details. However, we are quite good at noticing things that look completely different from the surrounds.

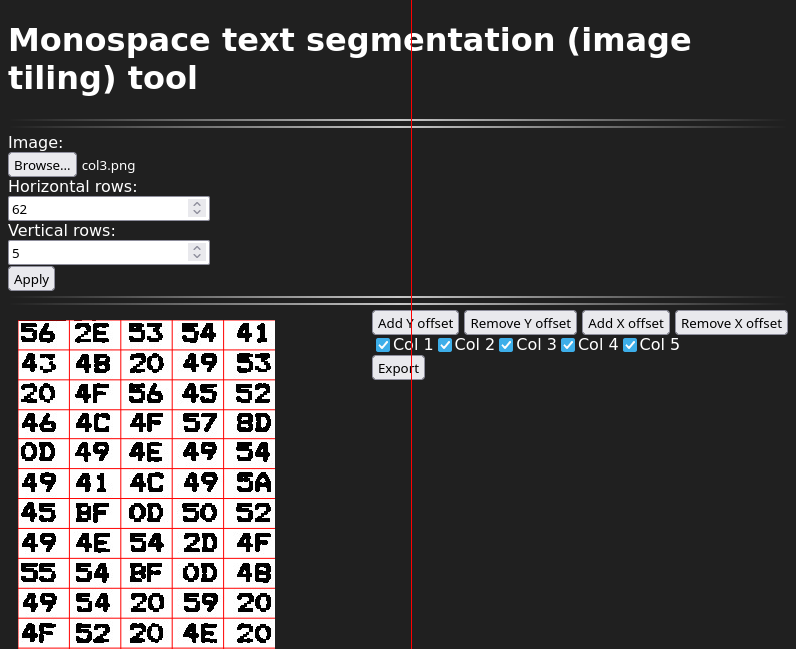

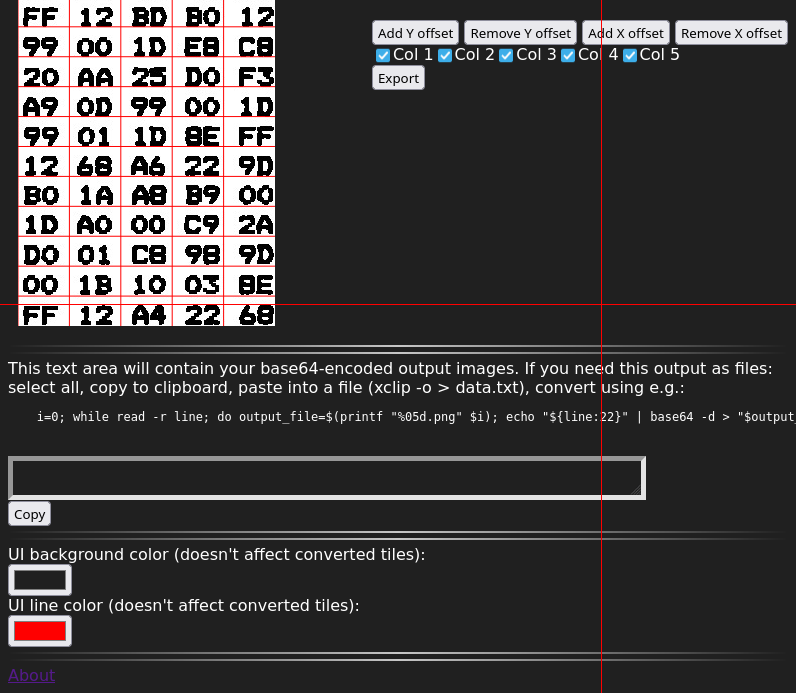

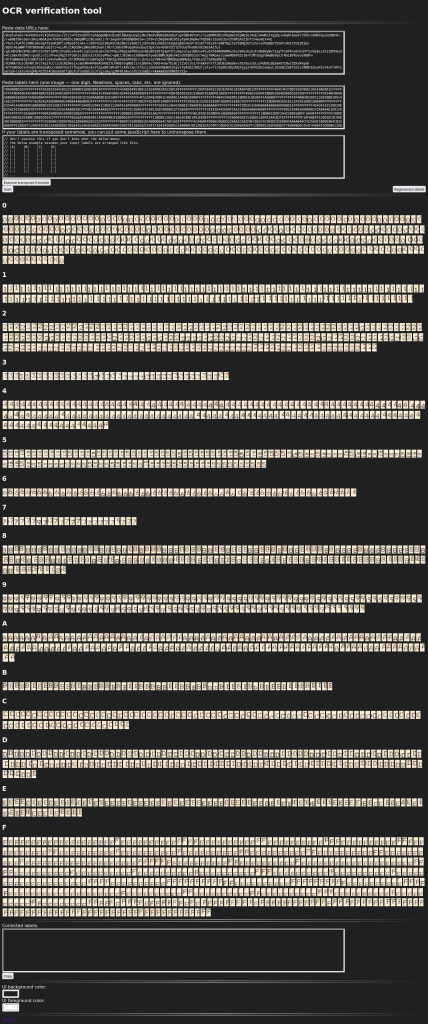

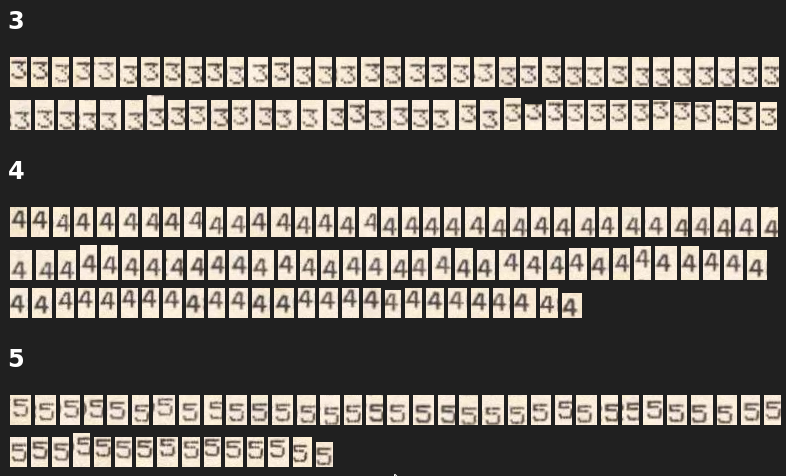

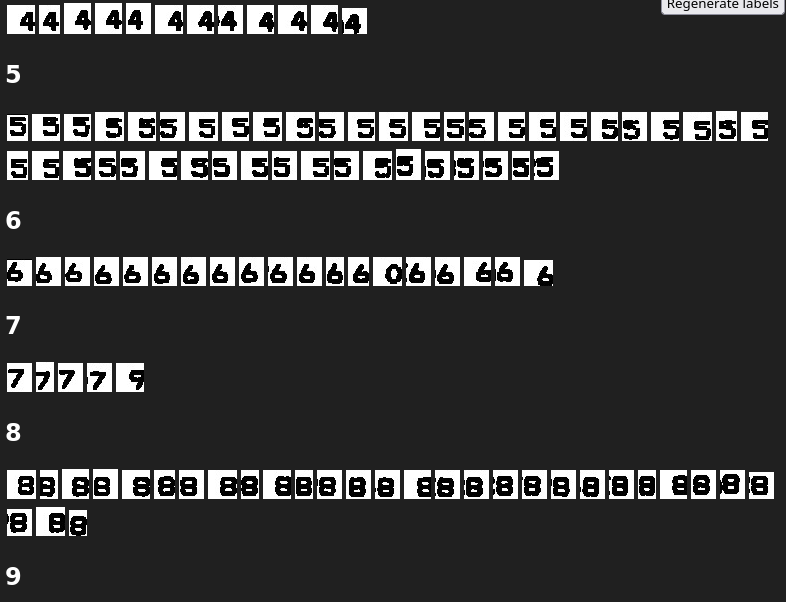

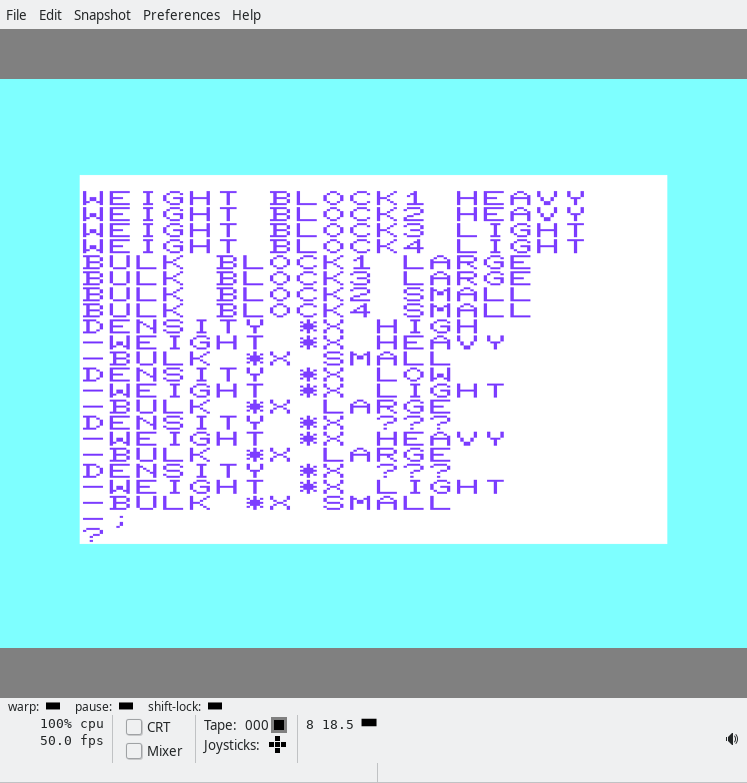

With hex OCR, we really only have to worry about 16 different classes (types of digit). This makes it relatively easy to verify if our OCR is correct (and perform fixes), because we can take our OCR’d digits and temporarily (while remembering their original position) display them all, sorted by class. Like this:

Or like this:

(Note: occasionally, OCR tools will turn a single character into two characters, or the other way round. That kind of problem will require manual edits.)

I created two tools, a segmentation tool, and the above verification tool, and described them a little more in this post: OCRing hex dumps (or other monospace text) and verifying the result. The tools themselves are at https://blog.qiqitori.com/ocr/monospace_segmentation_tool/ and https://blog.qiqitori.com/ocr/verification_tool/.

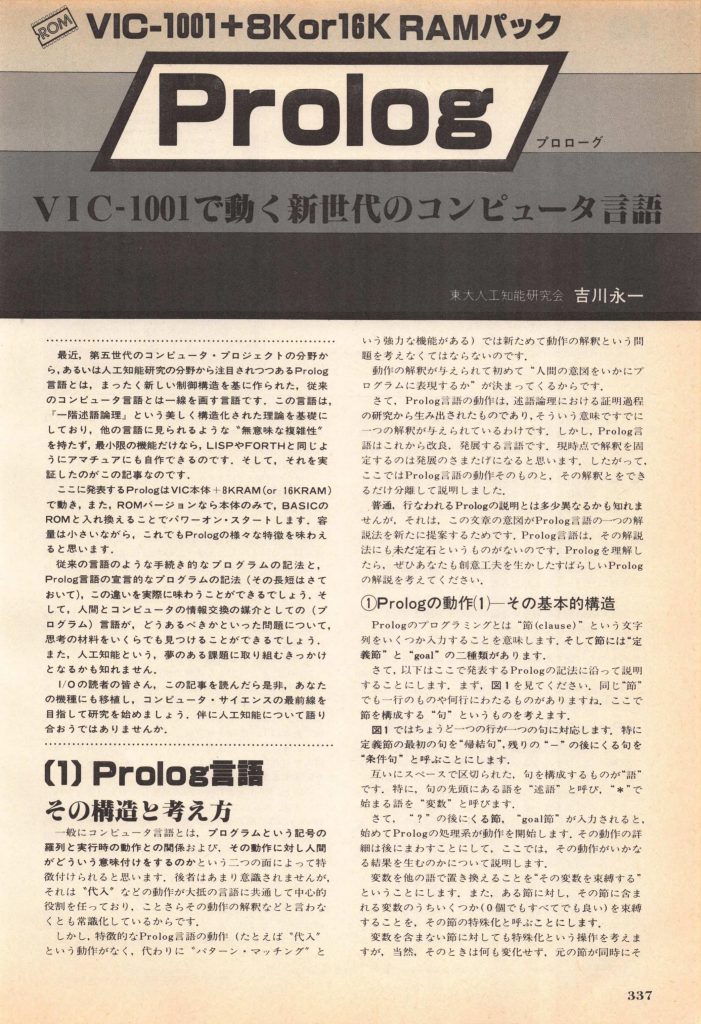

This is the scan in question: https://archive.org/details/Io19833/page/n342/mode/1up. Here’s the rather good-looking first page:

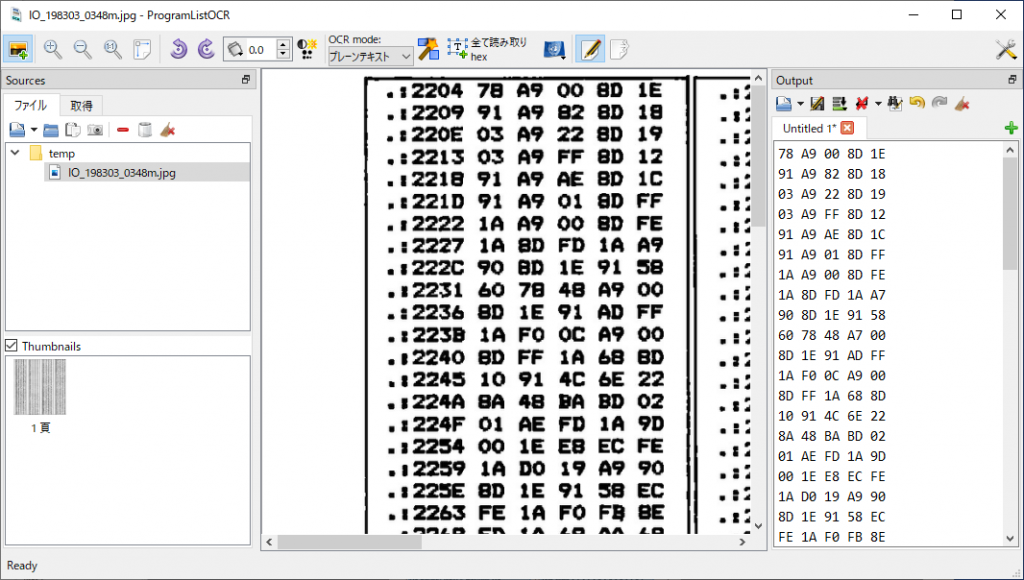

For the original OCR, I used a program called ProgramListOCR. The program supports OCRing hex dumps. This program requires that you touch up input images in (e.g.) Gimp before loading them. It’s not difficult, and the program’s README describes what needs to be done. Unfortunately, this process removes a small amount of detail from the image, making it harder to distinguish between, e.g., Bs and 8s. And unfortunately, I believe the program only runs in Windows. Here’s a screenshot of the program running:

ProgramListOCR made 142 digit mistakes. The hex dump consisted of 7310 digits, so the overall error rate is 1.943%, or the accuracy is 98.057%.

How to download and run Prolog

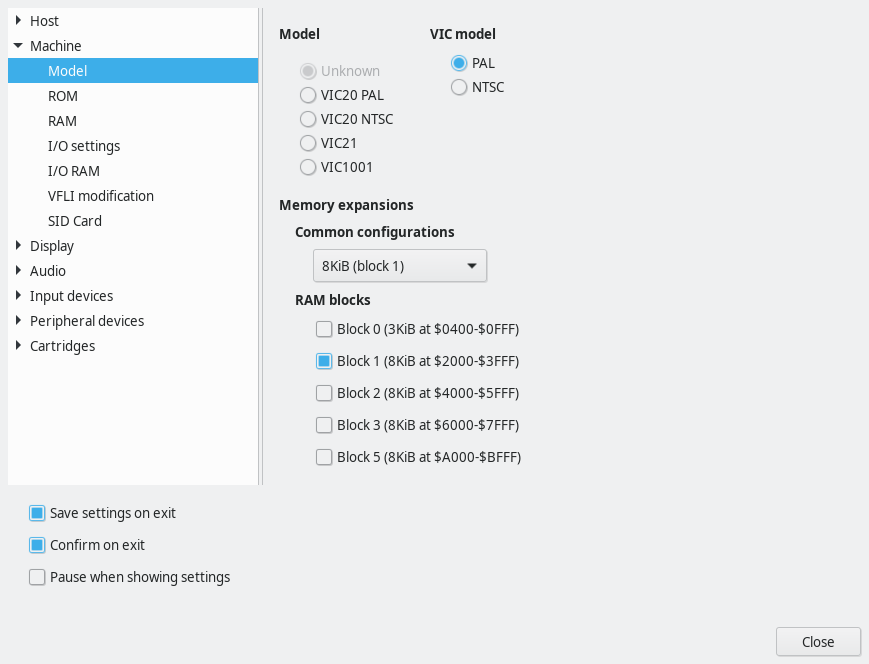

In order to run this on your VIC-20 emulator, you need to set it to have an 8K memory expansion. Then you need to load the binary data into RAM; starting address is 2204. In VICE, you can add the memory expansion in this config window:

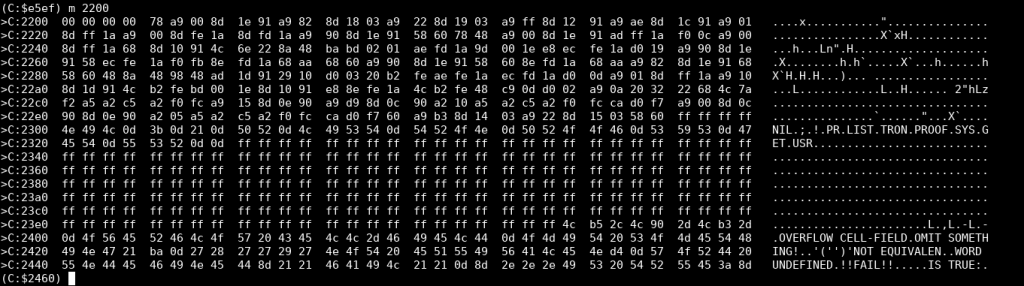

To load the binary data into address $2204 and beyond, start the monitor (Alt+H), and then I wish it’d work with ‘load “/path/to/prolog.bin” 0 2204’. But for some reason that doesn’t work; the first few bytes are garbled and the reset isn’t aligned correctly. If you have this issue, try the other file and ‘load “/path/to/prolog_prefixed_with_zeros.bin” 0 2202’. Execute “m 2200” in the monitor to see if VICE loaded your file into the correct address. The following is an example of a successful load:

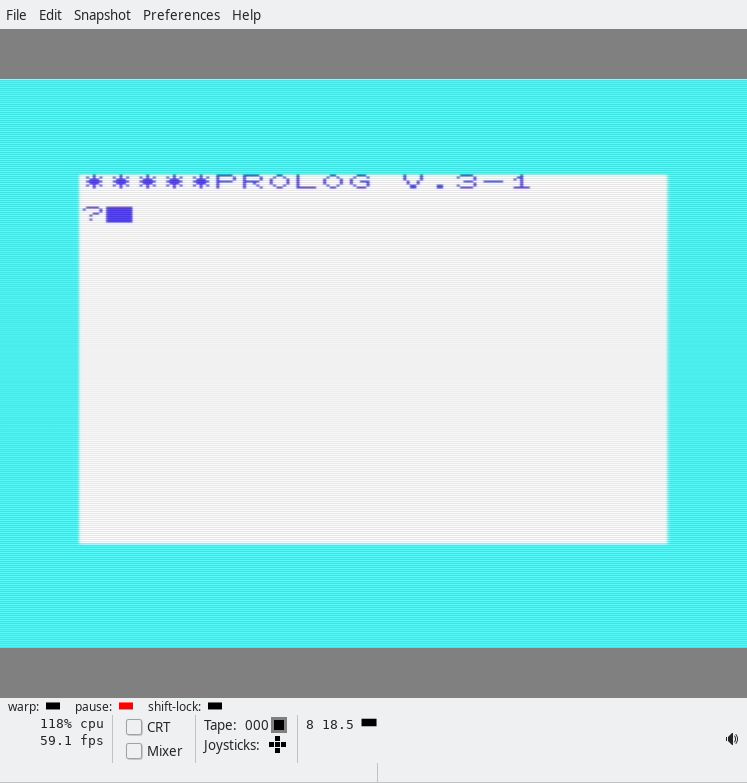

Then you close the monitor and type “SYS 11445” in the BASIC prompt, and you should get something like this:

Having fun with Prolog

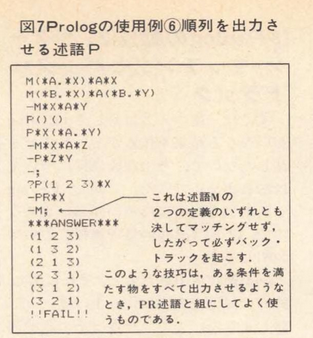

There are various sample programs in the magazine. Note that the Prolog interpreter sometimes gives you a question mark prompt, and sometimes a hyphen prompt. You have to delete these manually by pressing backspace (Delete), depending on what you want to do! Let’s start with this short program:

m(*a.*x)*a*x

m(*b.*x)*a(*b.*y)

-m*x*a*y

p()()

p*x(*a.*y)

-m*x*a*z

-p*z*y

-;

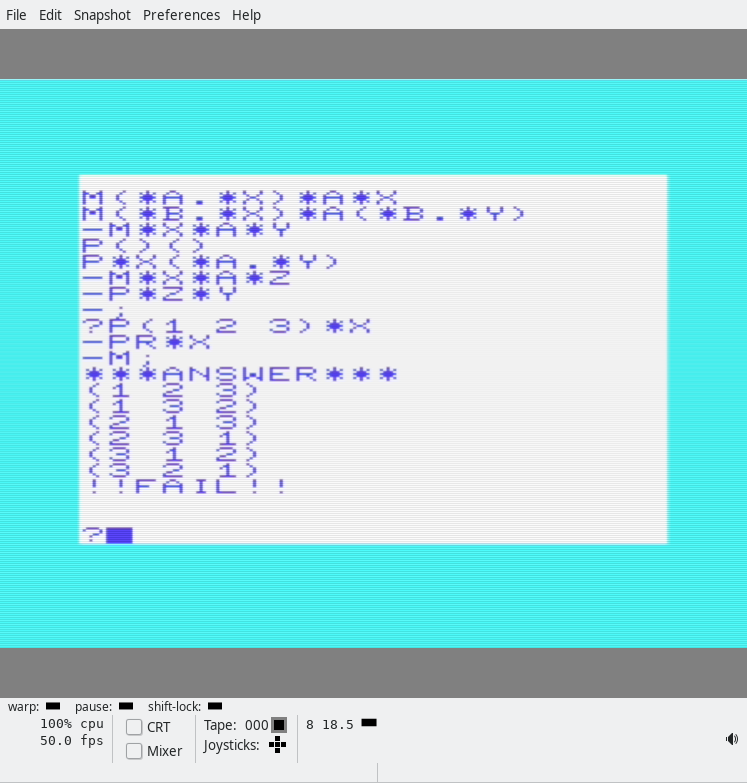

?p(1 2 3)*x

-pr*x

-m;

***answer***

(1 2 3)

(1 3 2)

(2 1 3)

(2 3 1)

(3 1 2)

(3 2 1)

!!fail!!The next program (actually the first in the magazine, and easiest) is a program that tells you whether the density of blocks 1-4 is high or low, or unknown:

weight block1 heavy

weight block2 heavy

weight block3 light

weight block4 light

bulk block1 large

bulk block3 large

bulk block2 small

bulk block4 small

density *x high

-weight *x heavy

-bulk *x small

density *x low

-weight *x light

-bulk *x large

density *x ???

-weight *x heavy

-bulk *x large

density *x ???

-weight *x light

-bulk *x small

-;

?I believe I speak for us all when I say, the syntax looks a bit weird? Anyway, the first few things are the data, er, I means facts. Then you get a function, er, predicate “signature”, and below the predicate signature you get the actual… predicate definition (the lines that start with a hyphen). (Predicates may also be called rules.) Want to finish up the current rules and start a new one with a different signature? Just backspace away the hyphen. When you’re all done, type a semicolon, and you’ll be back at the ‘?’ prompt. Now we can run queries!

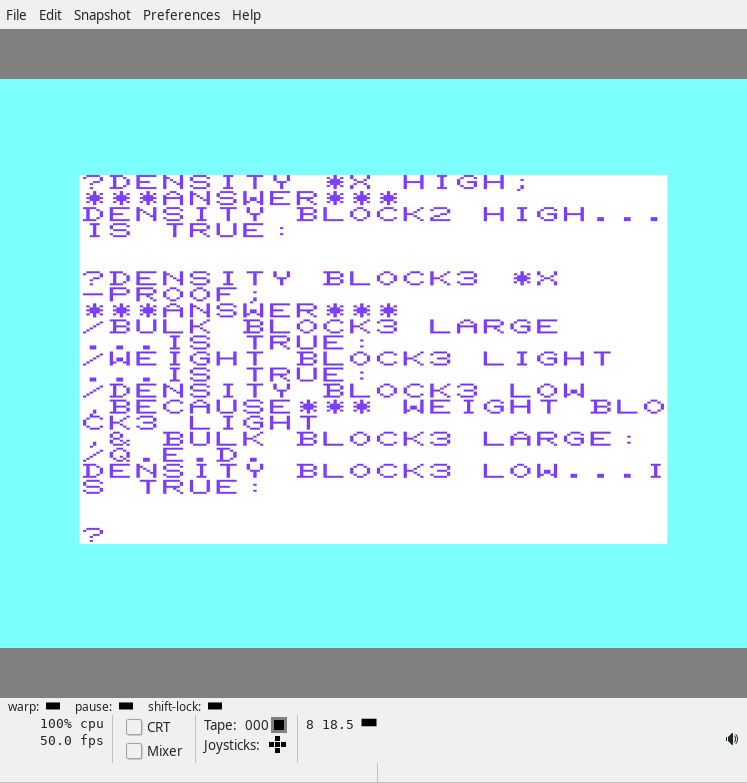

In the screenshot, we first ask which blocks have a high density. The answer is BLOCK2!

Then we ask it the density of BLOCK3 and ask it the reason using the PROOF

?DENSITY BLOCK3 *X

-PROOF;And the answer is:

/DENSITY BLOCK3 LOW ,BECAUSE*** WEIGHT BLOCK3 LIGHT ,& BULK BLOCK3 LARGE:

/Q.E.D.

DENSITY BLOCK3 LOW...IS TRUE: